¶ Summary - Aznalcóllar Tender Controversy (2015–ongoing)

In late 2014, the regional government of Andalusia (Junta de Andalucía) opened an international tender to select an operator for the abandoned Aznalcóllar zinc–lead–silver mine near Seville. Emerita Resources submitted the required technical bid on December 16, 2014 (emeritaresources.com). In February 2015, the tender committee announced that a rival bidder – a joint venture of Grupo México and local partner Minorbis – had been selected as the winner. On February 26, 2015, the formal resolution was issued granting the project to Minera Los Frailes, S.L., a company formed by the Grupo México–Minorbis consortium (emeritaresources.com). Emerita, whose proposal had met all requirements, immediately filed a legal challenge on February 27, 2015, alleging the selection was unlawful. A Seville court accepted Emerita’s appeal on March 2, 2015, effectively launching a judicial review of the tender process (emeritaresources.com).

¶ Initial Investigation and Criminal Charges

As the case unfolded, evidence of serious irregularities emerged. By mid-2015, a Spanish judge investigating the tender had charged seven members of the government panel (including the regional Director of Mines and other officials) with prevarication, a form of official misconduct for knowingly issuing an unjust decision (globenewswire.com)(globenewswire.com). This indicated the court found prima facie signs that the Aznalcóllar contract may have been awarded through corrupt or illegal means. Emerita’s executives asserted that the public tender process had been “circumvented by certain individuals”, noting that Emerita had invested over USD $1 million to produce a comprehensive bid that was disregarded under suspect circumstances(globenewswire.com). The company urged that, under Spanish law, if the winning bid were nullified, the project should be awarded to the next qualified bidder – in this case, Emerita (globenewswire.com).

¶ Irregularities in the Winning Bid

Subsequent court testimony and documents revealed multiple irregularities and advantages improperly given to the Minorbis–Grupo México bid:

¶ Unqualified Participant

It came to light that Grupo México did not officially participate in the tender at all, despite being touted as part of the winning consortium. The exploitation contract was awarded to Minera Los Frailes S.L., a new entity incorporated only after the tender process concluded, solely owned by Grupo México (globenewswire.com). According to Spanish law, only companies that actually took part in the bid can receive the award, calling into question the legality of granting the license to this late-formed company (globenewswire.com). Moreover, Minorbis – the local partner that nominally submitted the bid – failed to meet several minimum requirements of the tender: it had no mining staff or experience and provided none of the required financial solvency assurances (such as bank statements or an insurance bond) mandated in the tender documents (globenewswire.com). These deficiencies meant Minorbis should not have qualified to advance beyond the initial phase of the tender (globenewswire.com).

¶ Bias in Bid Scoring

Investigators found evidence that the tender evaluation panel had manipulated the scoring to favor the Minorbis bid. For example, Emerita had proposed a significantly larger investment in the mine and local community compared to Minorbis’s offer (equity.guru). Yet the panel awarded Minorbis a higher score on the “investment” criterion by an unusual calculation: they divided Emerita’s total investment by 73 mining claims versus 53 for Minorbis, which artificially reduced Emerita’s per-claim investment figure and made Minorbis’s smaller overall investment appear superior (globenewswire.com). The judge found this reasoning unsatisfactory and not grounded in the stated tender criteria, noting such an arbitrary scoring method violated principles of fairness and transparency.

¶ Technical and Safety Concerns

The winning proposal was also criticized for technical plans that conflicted with regulatory and safety guidelines. Minorbis’s mine development plan contemplated reopening the Los Frailes deposit by driving a ramp through the weakened south wall of the old open pit, an area known from past studies to be geotechnically unstable (two major pit wall failures had occurred there in the late 1990s) (globenewswire.com)(globenewswire.com). In addition, the Minorbis proposal projected massive groundwater pumping and water discharge – on the order of 4.97 million cubic meters per year during pre-production – into the nearby river system (globenewswire.com). This far exceeded the 0.75 million m³/year discharge limit set by the Guadalquivir River Authority (CHG) for that site (globenewswire.com). The tender panel nevertheless deemed the Minorbis plan environmentally acceptable, even calling it a “closed system” with no significant water release (globenewswire.com). By contrast, Emerita’s bid had included a detailed water management plan developed in consultation with CHG, earned an official endorsement from the water authority, and avoided using the unstable pit wall by proposing an alternate underground access design (globenewswire.com)(globenewswire.com). Despite these advantages, Emerita’s technical proposal was marked down by the panel, whereas the riskier Minorbis plan received higher points (globenewswire.com)(globenewswire.com). Emerita argued that the government committee ignored critical safety and environmental issues in order to favor the local consortium’s bid.

These and other findings reinforced Emerita’s claim that the Aznalcóllar tender was improperly awarded through bias or corruption. In late 2016 and again in 2019, higher courts in Seville reviewed the case. Notably, in October 2019 the Provincial Court (Audiencia of Seville) unanimously overturned a prior dismissal of the case and ordered the criminal prosecution to proceed, expanding the scope of charges related to the alleged bid-rigging (emeritaresources.com). By then, a total of 16 individuals – including government officials and company representatives – had been indicted on charges ranging from influence peddling and bribery to fraud and embezzlement (emeritaresources.com). The Aznalcóllar corruption trial was scheduled to begin in March 2025, reflecting the lengthy process of Spain’s judicial system (emeritaresources.com). As of 2025, the legal outcome remains pending; if the courts ultimately void the original award as unlawfully obtained, the mining rights could be reassigned to Emerita as the rightful next bidder (equity.guru). Until then, the Aznalcóllar project remains in limbo, with Emerita maintaining that it stands ready to develop the mine in compliance with all technical and environmental standards (globenewswire.com)(globenewswire.com).

¶ Size of the Prize

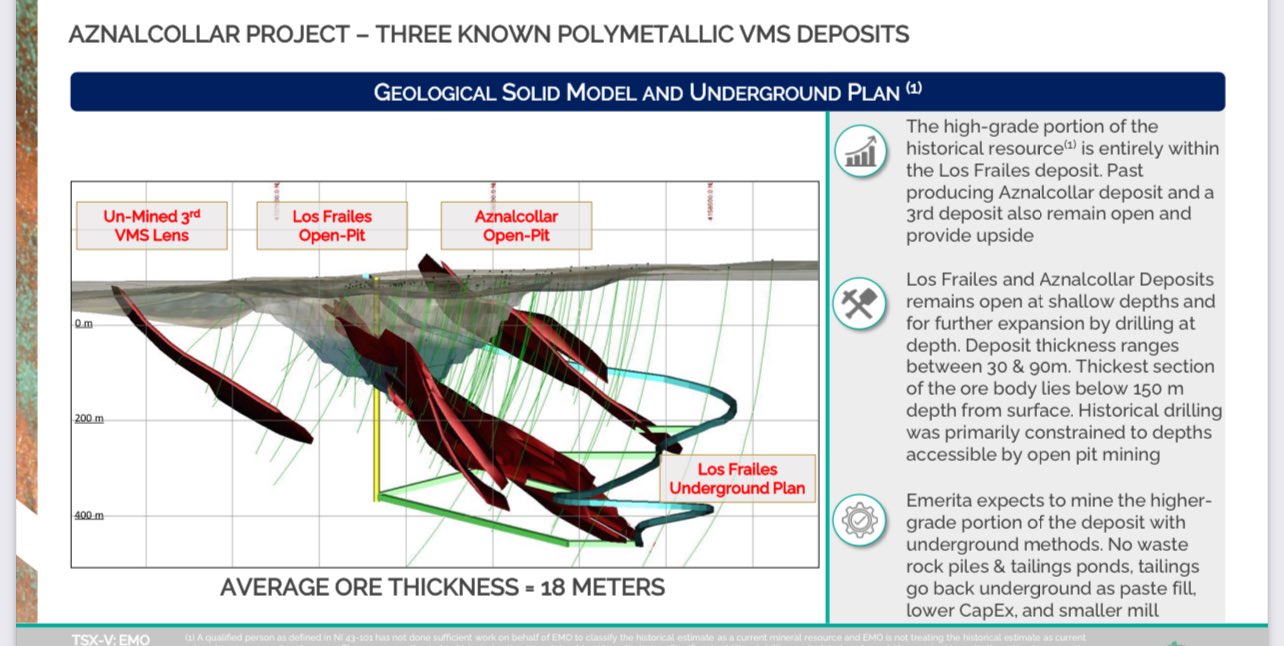

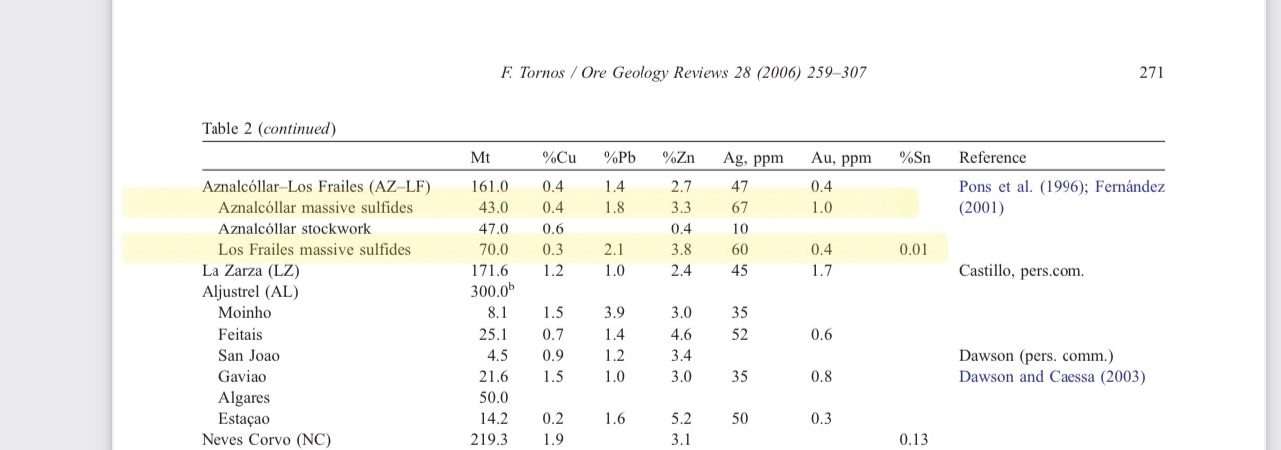

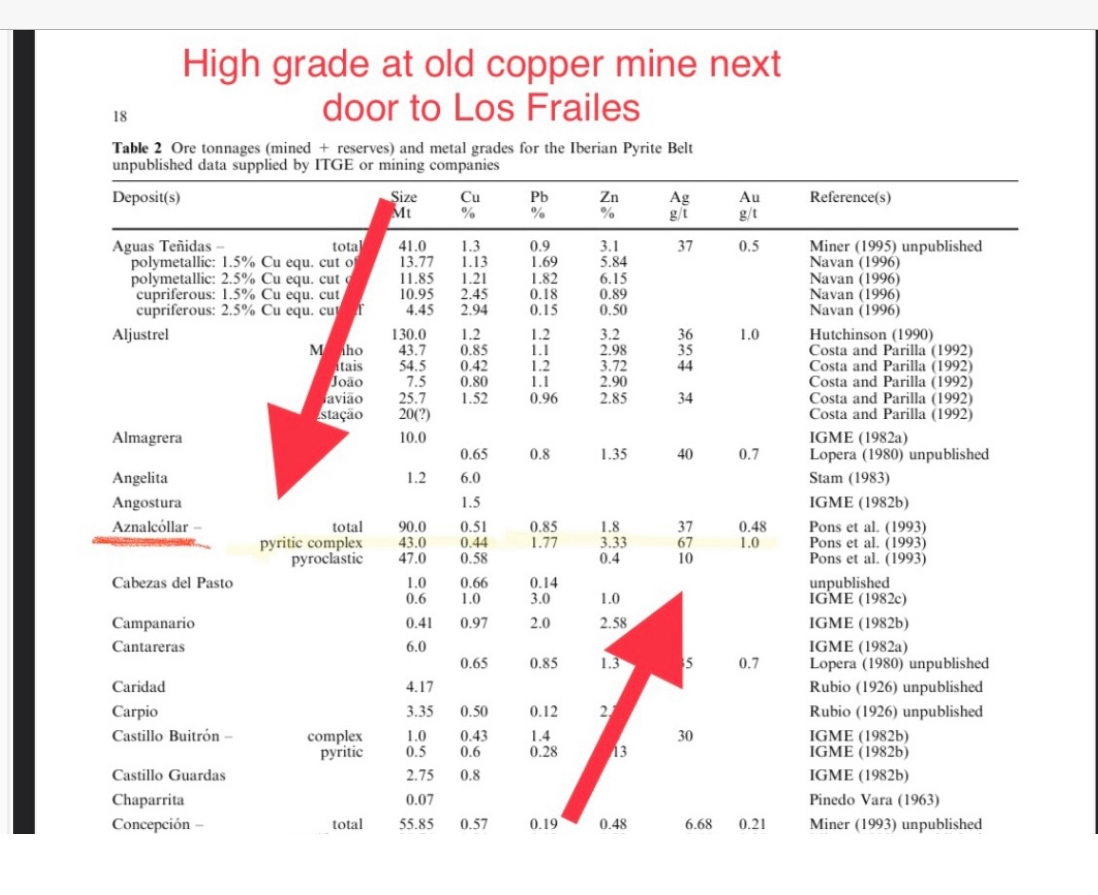

The Tier-1 Aznalcóllar Land Package comprises four known deposits with significant mineral resources, primarily zinc, lead, copper, silver, and gold. Below is a summary of the resources for each deposit based on available data.

¶ Aznalcollar Mine

Total Resources: 90 million tonnes (Mt) of production-drilled resources.

High-Grade Subset: 43 Mt containing:

- Gold: 1.38 million ounces

- Silver: 93 million ounces

- Zinc: 3.15 billion pounds

- Lead: 1.67 billion pounds

- Copper: 416 million pounds

Source: Verified in the 1998 Mining Journal Iberian Pyrite Belt.

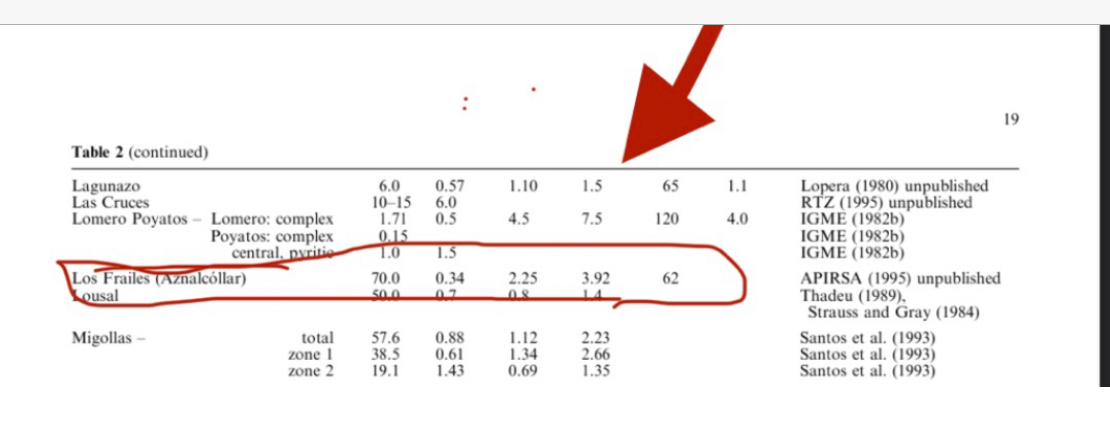

¶ Los Frailes Mine

Total Resources: 70 Mt of production-drilled resources.

High-Grade Lens: 28 Mt, including:

- 20 Mt pit-constrained

- 8 Mt below the pit

Resource Estimates:

- Zinc: 4.1 billion pounds

- Lead: 2.4 billion pounds

- Copper: 179 million pounds

- Silver: 76 million ounces

Additional Potential: Tens of millions of tonnes below the deepest hole historically drilled, with high-grade material over 40 meters thick.

Note: Tender awarded to put the mine into production, as mentioned by the CEO in webinars and interviews.

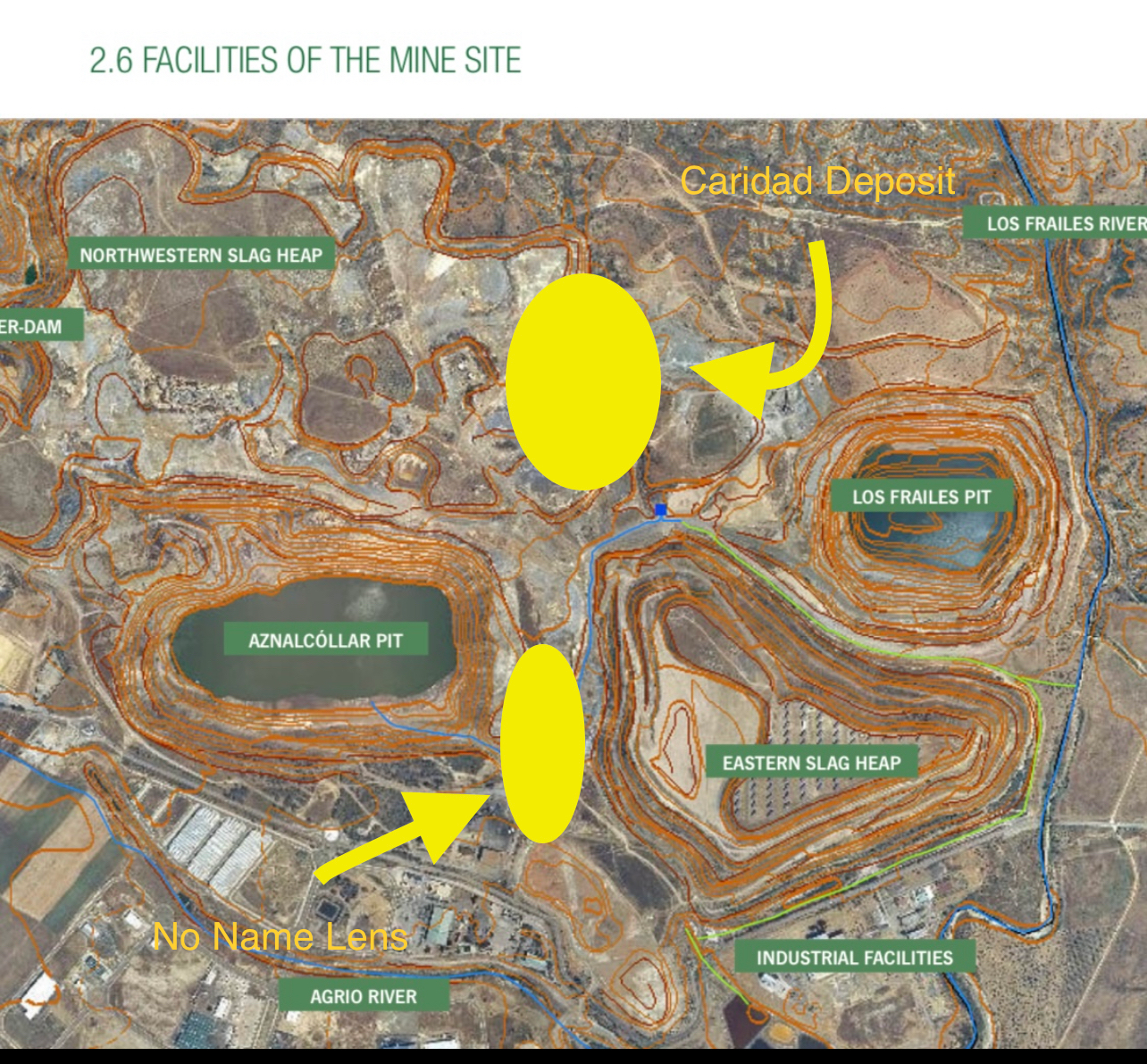

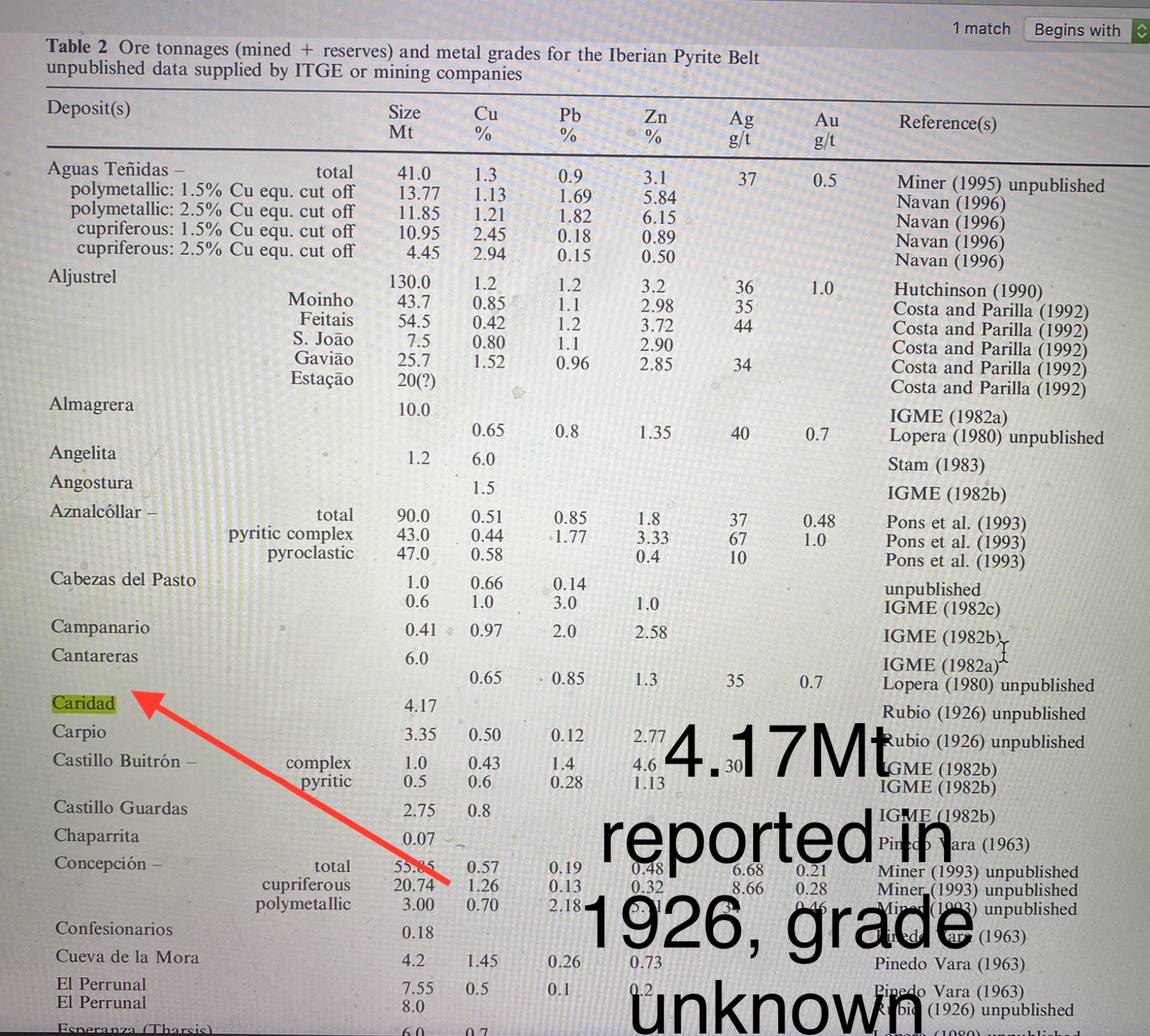

¶ Caridad Deposit

Total Resources: 4.17 Mt.

Characteristics: Historically referred to as “copper-rich.”

¶ Doc Jones/Non-Name Lens

Estimated Resources: 7.5 Mt, based on drill data.

Grade: Equivalent to Los Frailes high-grade lens.

Location: Positioned between Aznalcollar and Los Frailes mines.

¶ Summary

The Aznalcollar Land Package hosts a combined resource of approximately 171.67 Mt across the four deposits, with significant high-grade zones in the Aznalcollar and Los Frailes mines. These deposits are rich in zinc, lead, copper, silver, and gold, with potential for further exploration, particularly below the deepest drilled sections of Los Frailes.

¶ All Tonnes In-Situ Value

This document estimates the in-situ value of all reported tonnes in the Aznalcollar Land Package, including Aznalcollar Mine (90 Mt), Los Frailes Mine (70 Mt), Caridad Deposit (4.17 Mt), and Doc Jones/Non-Name Lens (7.5 Mt), using metal spot prices as of July 21, 2025.

¶ Metal Spot Prices

- Gold: $3,366.28/oz

- Silver: $38.45/oz

- Zinc: $1.35/lb

- Lead: $1.01/lb

- Copper: $5.63/lb

¶ In-Situ Value by Deposit

¶ Aznalcollar Mine (90 Mt)

High-Grade Subset (43 Mt):

- Gold: 1.38 million oz × $3,366.28 = $4,645,466,400

- Silver: 93 million oz × $38.45 = $3,575,850,000

- Zinc: 3.15 billion lbs × $1.35 = $4,252,500,000

- Lead: 1.67 billion lbs × $1.01 = $1,686,700,000

- Copper: 416 million lbs × $5.63 = $2,342,080,000

Subtotal: $16,502,596,400

Remaining Resources (47 Mt):

- Gold: 0.754 million oz × $3,366.28 = $2,538,175,120

- Silver: 50.83 million oz × $38.45 = $1,954,413,500

- Zinc: 0.860 billion lbs × $1.35 = $1,161,000,000

- Lead: 0.456 billion lbs × $1.01 = $460,560,000

- Copper: 0.113 billion lbs × $5.63 = $636,190,000

Subtotal: $6,750,338,620

Total: $23,252,935,020

¶ Los Frailes Mine (70 Mt)

High-Grade Lens (28 Mt):

- Zinc: 4.1 billion lbs × $1.35 = $5,535,000,000

- Lead: 2.4 billion lbs × $1.01 = $2,424,000,000

- Copper: 179 million lbs × $5.63 = $1,007,770,000

- Silver: 76 million oz × $38.45 = $2,922,200,000

Subtotal: $11,888,970,000

Remaining Resources (42 Mt):

- Zinc: 1.537 billion lbs × $1.35 = $2,074,950,000

- Lead: 0.901 billion lbs × $1.01 = $910,010,000

- Copper: 0.067 billion lbs × $5.63 = $377,210,000

- Silver: 56.91 million oz × $38.45 = $2,187,169,500

Subtotal: $5,549,339,500

Total: $17,438,309,500

¶ Caridad Deposit (4.17 Mt)

- Zinc: 0.305 billion lbs × $1.35 = $411,750,000

- Lead: 0.179 billion lbs × $1.01 = $180,790,000

- Copper: 0.027 billion lbs × $5.63 = $151,710,000

- Silver: 11.30 million oz × $38.45 = $434,485,000

Total: $1,178,735,000

¶ Doc Jones/Non-Name Lens (7.5 Mt)

- Zinc: 0.549 billion lbs × $1.35 = $741,150,000

- Lead: 0.322 billion lbs × $1.01 = $325,220,000

- Copper: 0.024 billion lbs × $5.63 = $135,120,000

- Silver: 20.33 million oz × $38.45 = $781,688,500

Total: $1,983,178,500

¶ Total In-Situ Value

- Aznalcollar Mine: $23,252,935,020

- Los Frailes Mine: $17,438,309,500

- Caridad Deposit: $1,178,735,000

- Doc Jones/Non-Name Lens: $1,983,178,500

Grand Total: $43,853,158,020 (~$43.85 billion)

¶ Notes

In-Situ Value: Gross value, excluding mining, processing, recovery, or operational costs.

Assumptions:

- Aznalcollar and Los Frailes remaining resources (47 Mt and 42 Mt) assume 50% of high-grade subset/lens grades.

- Caridad Deposit uses Los Frailes high-grade lens grades with doubled copper grade (0.64% Cu) to reflect “copper-rich” nature.

- Doc Jones/Non-Name Lens uses Los Frailes high-grade lens grades.

- No gold assumed for Los Frailes, Caridad, or Doc Jones, potentially underestimating value.

Data Gaps: Remaining resources in Aznalcollar and Los Frailes lack detailed assays; estimates are conservative.

Price Data: Zinc and lead prices based on slightly older data (July 17 and March 24, 2025, respectively).

Upside Potential: Los Frailes may have additional high-grade resources below the deepest drilled hole, not included here.

¶ High Grade ONLY In-Situ Value

To estimate the in-situ value of the mineral resources in the Aznalcollar Land Package (comprising Aznalcollar Mine, Los Frailes Mine, Caridad Deposit, and Doc Jones/Non-Name Lens), we will use the provided resource data and current spot prices for gold, silver, zinc, lead, and copper as of July 21, 2025. For this calculation we will only consider the high grade metal content of the land package. The in-situ value represents the gross value of the metals in the ground without accounting for mining, processing, or recovery costs.

¶ Resource Data Summary

The High Grade resource data for each deposit is as follows:

¶ Aznalcollar Mine:

- High-Grade Subset (43 Mt):

- Gold: 1.38 million ounces

- Silver: 93 million ounces

- Zinc: 3.15 billion pounds

- Lead: 1.67 billion pounds

- Copper: 416 million pounds

- Total Resources (90 Mt): No detailed metal breakdown provided for the remaining 47 Mt; we will focus on the high-grade subset for precise calculations.

¶ Los Frailes Mine:

- High-Grade Lens (28 Mt):

- Zinc: 4.1 billion pounds

- Lead: 2.4 billion pounds

- Copper: 179 million pounds

- Silver: 76 million ounces

- Total Resources (70 Mt): No detailed metal breakdown for the remaining 42 Mt; we will focus on the high-grade lens.

¶ In-Situ Value Calculations

We calculate the in-situ value by multiplying the metal quantities by their respective spot prices. All values are in USD.

¶ Aznalcollar Mine (High-Grade Subset, 43 Mt)

- Gold: 1.38 million oz × $3,366.28/oz = $4,645,466,400

- Silver: 93 million oz × $38.45/oz = $3,575,850,000

- Zinc: 3.15 billion lbs × $1.35/lb = $4,252,500,000

- Lead: 1.67 billion lbs × $1.01/lb = $1,686,700,000

- Copper: 416 million lbs × $5.63/lb = $2,342,080,000

- Total: $4,645,466,400 + $3,575,850,000 + $4,252,500,000 + $1,686,700,000 + $2,342,080,000 = $16,502,596,400

¶ Los Frailes Mine (High-Grade Lens, 28 Mt)

- Zinc: 4.1 billion lbs × $1.35/lb = $5,535,000,000

- Lead: 2.4 billion lbs × $1.01/lb = $2,424,000,000

- Copper: 179 million lbs × $5.63/lb = $1,007,770,000

- Silver: 76 million oz × $38.45/oz = $2,922,200,000

- Total: $5,535,000,000 + $2,424,000,000 + $1,007,770,000 + $2,922,200,000 = $11,888,970,000

¶ High Grade In-Situ Value

Summing the in-situ values for the high-grade subsets and estimated resources:

- Aznalcollar Mine: $16,502,596,400

- Los Frailes Mine: $11,888,970,000

- Total In-Situ Value: $16,502,596,400 + $11,888,970,000 = $28,391,566,400

Grand Total (High Grade ONLY): $28,391,566,400 (~$28.39 billion)

The estimated in-situ value of the known resources in the Aznalcollar Land Package, based on high-grade subsets, is approximately $28.39 billion USD, using spot prices from July 21, 2025. This includes:

- Aznalcollar Mine (43 Mt): $16.50 billion

- Los Frailes Mine (28 Mt): $11.89 billion

This value excludes the remaining 89 Mt of lower-grade resources in Aznalcollar and Los Frailes due to insufficient data and assumes no significant value in Caridad or Doc Jones deposits.

¶ Notes and Assumptions

- Scope Limitation: The calculation focuses on the high-grade subsets for Aznalcollar (43 Mt) and Los Frailes (28 Mt) due to detailed data availability. The remaining 47 Mt (Aznalcollar) and 42 Mt (Los Frailes) lack specific metal content, so they are excluded, potentially underestimating the total value.

- In-Situ Value: This is a gross value, not accounting for mining, processing, recovery rates, or operational costs, which would reduce the net value significantly.

- Price Data: Spot prices for zinc and lead rely on slightly older data (July 17 for zinc, March 24 for lead), as no newer prices were available. Copper, gold, and silver prices are current as of July 21, 2025.

¶ The Tender

¶ Overview

The Aznalcóllar legal proceedings represent one of the most complex and consequential mining-related corruption cases in modern Spanish judicial history. At the heart of the case lies the disputed 2015 tender award for the Aznalcóllar mine, a world-class polymetallic deposit located in Andalusia, which was granted to a consortium led by Grupo México and Minorbis (Magtel) under circumstances later deemed irregular by multiple courts. The litigation spans both criminal and administrative jurisdictions, with parallel actions brought by Emerita Resources Corp. (EMO)—a Canadian-listed company and the runner-up in the Aznalcóllar tender—seeking both criminal accountability and reassignment of mining rights.

Importantly, this is not Emerita’s first major legal battle in Spain. In a separate case concerning the IBW (Iberian Belt West) mining project, Emerita successfully contested the outcome of another controversial tender process and was ultimately awarded the rights through a final ruling by the Contentious-Administrative Court. That earlier case established a critical legal precedent: that Emerita was prepared and able to pursue high-stakes administrative litigation in Spain—and win. The IBW victory not only underscored flaws in the original adjudication process, but also demonstrated that Spanish courts, when pressed, are willing to reverse politically influenced outcomes in favor of the lawful bidder. That history looms large over the current Aznalcóllar proceedings, lending further credibility to Emerita’s position and intensifying investor focus on the outcome.

The current Aznalcóllar case was initially resisted by the public prosecutor, who made repeated attempts to shelve or downplay the investigation. It only proceeded due to the tenacity of investigative judges, most notably Mercedes Alaya and Patricia Fernández, who both flagged severe irregularities and forced the matter into trial. The 2025 oral hearings—now in the deliberations phase—feature 16 defendants, including senior Andalusian officials, former SEPI President Vicente Fernández, and various members of the Magtel-linked tender committee. With final arguments concluding mid-July 2025, the trial’s outcome is expected to determine not only criminal liability but also the future of the concession itself, which could be reassigned to Emerita under the right legal conditions. All of this is unfolding amid a broader political and judicial reckoning in Spain—one in which past impunity is giving way to accountability.

¶ The Timeline

¶ Litigation and Administrative Proceedings

¶ 2014

March–April: Junta de Andalucía launches international tender process for the Aznalcóllar mining concession.

April 11: Alleged meeting between José Antonio Gutiérrez López (senior Junta official) and Emerita President Joaquín Merino. That same day, a call is allegedly placed by Vicente Fernández (then Secretary General for Innovation) to Merino, which becomes central to later criminal proceedings.

June–August: Technical phase evaluations proceed. Emerita submits highest-value technical and environmental proposal; Minorbis–Grupo México advances despite alleged disqualifying deficiencies.

November: Emerita files initial administrative challenge against the tender process.

¶ 2015

February 25: Junta awards the Aznalcóllar concession to Minera Los Frailes (MLF), a shell company that did not exist at the time of award. Emerita alleges serious irregularities.

May: MLF formally accepts the award; its shell structure (owned 97% by AMC Iberia, a Grupo México vehicle) is exposed.

July: Emerita submits additional documentation alleging criminal misconduct and procedural fraud in the awarding process.

¶ 2016–2017

Ongoing: Administrative court challenge by Emerita continues through Tribunal Administrativo de Recursos Contractuales de la Junta de Andalucía (TARCJA), eventually escalating.

2017: Initial criminal complaint brought before the Court of Instruction No. 3 in Seville.

¶ 2018

Criminal investigation formally opened: Judge Patricia Fernández leads initial investigation phase, despite resistance from the Fiscalía (Public Prosecutor), who repeatedly seeks to dismiss the case.

December: High-profile evidence emerges including signed police statements, internal emails, and phone records indicating forward contact and procedural tampering.

¶ 2020

June: Judge Mercedes Alaya takes over and issues indictments against 16 individuals, including high-ranking officials and representatives linked to Minorbis/Magtel.

August: Emerita wins its administrative court case for IBW, confirming that it was illegally denied access to the Iberian Pyrite Belt project (this precedent informs Aznalcóllar strategy).

¶ 2021

May–June: Judge Alaya issues detailed judicial opinions (three rulings: 26 May, 27 May, 25 June) confirming chain of influence peddling and validating core accusations made by Emerita and Ecologists in Action.

July: Prosecutor renews efforts to dismiss charges. Judges reject this, reaffirming the case must proceed.

¶ 2022

January–November: Pre-trial motions and appeals cycle through higher courts. Minorbis–Grupo México attempt to delay proceedings citing procedural concerns. Courts reject these.

¶ 2023

June–September: Trial formally scheduled for early 2025. Preparatory motions filed by all parties including AMC Andalucía Mining SA (seeking civil damages after being eliminated during tender).

¶ 2024

July–November: Public corruption scandals engulf PSOE figures, including Santos Cerdán, intensifying public scrutiny of the Aznalcóllar affair.

September: Criminal court confirms AMC (not to be confused with Grupo México's AMC Iberia) has standing as an aggrieved underbidder.

¶ 2025

March 4: Oral trial phase begins before the Provincial Court of Seville.

March–June: Key defendants testify; Vicente Fernández reverses his prior signed police statement in open court, denying the 11 April call. Contradiction becomes a focal point of the trial.

July 5–15: Closing statements delivered. Emerita’s counsel Ramón Escudero Espín presents a comprehensive, evidence-backed summary. AMC also supports the invalidity of the award. Public prosecutor reaffirms request for acquittal—widely viewed as institutionally performative.

Verdict expected: Between late July and early September 2025.

¶ The Players

The Aznalcóllar corruption trial brings together a wide cast of political figures, corporate actors, legal institutions, and civil organisations. Understanding the roles, motives, and legal standing of each is essential to navigating the complexity of the case. Below is an overview of the main players involved in both the criminal trial and the surrounding administrative and political landscape.

¶ Emerita Resources Corp. (EMO)

A Canadian-listed mining company and the runner-up in the original 2014–2015 Aznalcóllar tender process. Emerita submitted a €641M development proposal and has consistently argued that its bid was superior in technical, financial, and environmental terms. Following the award to Minorbis–Grupo México, Emerita filed both an administrative challenge and later joined the criminal proceedings as a private prosecutor (acusación particular). Emerita’s legal standing and documentary position have been repeatedly validated by Spanish courts. The company previously won an administrative court battle for the IBW mining rights, setting a precedent for judicial correction of flawed tender processes.

¶ Grupo México

A multinational mining conglomerate and parent company of several entities involved in the tender. Grupo México is the majority owner (97%) of Minera Los Frailes (MLF)—the company that ultimately accepted the Aznalcóllar contract, despite not existing at the time of the award. Grupo México is not a named defendant in the criminal case, but several of its affiliates (including AMC Iberia) have been cited as civilly liable parties. Grupo México’s role is central in terms of benefit gained from the allegedly rigged tender.

¶ Minorbis (Magtel)

Minorbis, a subsidiary of Córdoba-based infrastructure firm Magtel, was the official lead bidder in the winning consortium. Evidence in the case suggests Minorbis was a political proxy that helped facilitate Grupo México’s entry and shield its lack of mining experience in Spain. Financial transfers, emails, and the structure of the JV with AMC/Grupo México have been cited as part of the alleged scheme to rig the outcome. Minorbis is considered by prosecutors and judges to have lacked the technical qualifications required under Spanish mining law.

¶ Minera Los Frailes SL (MLF)

MLF is the corporate entity to which the mining concession was formally awarded. According to the Andalusian Mining Registry and multiple press reports, MLF did not exist on the date the award was granted—its registration and restructuring occurred after the fact. It is owned 97% by AMC Iberia (Grupo México) and 3% by Minorbis. Both the timing of its creation and its lack of tender participation have been raised as key legal violations.

¶ AMC Iberia (SC Andalucía Mining SA)

Clarification is critical here. There are two distinct entities referred to as “AMC”:

- AMC Iberia (SC Andalucía Mining SA) is the civil claimant in the current criminal trial. This entity was an eliminated tender bidder who has joined the proceedings as an aggrieved under-bidder, arguing that Minorbis and Grupo México received preferential and unlawful treatment.

- AMC Mining Iberia, also referred to historically as “Redhill 2000 SL,” is the Grupo México shell company that assumed control of MLF. This should not be confused with SC Andalucía Mining SA.

The first AMC (SC Andalucía Mining) is aligned with Emerita’s position and delivered a robust closing statement dismantling Minorbis’ solvency and administrative standing.

¶ The Defendants

There are 16 named defendants (all listed below) including:

- Vicente Fernández Guerrero, former President of SEPI, indicted for influence peddling. He is accused of calling Emerita’s president following the infamous López meeting on April 11, 2014—a call he initially admitted in police statements but denied under oath during the trial.

- Antonio Ramírez de Arellano, former Secretary General for Innovation, who allegedly approved the final award despite evidence of procedural irregularities.

Multiple members of the original tender committee, many of whom are accused of prevaricación, fraude en la contratación pública, and tráfico de influencias. Several defendants have contradicted their own statements under oath or failed to rebut critical evidence presented by both private prosecutors.

|

Accused Parties in Aznalcóllar Mining Case |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Charges | Title/Position | Role in the Tender |

| María José Asensio Coto | Prevarication, Influence Peddling, Administrative Fraud, Embezzlement | General Director of Mines, Doctor in Economics, President of Valuation Table | Ultimate decision-maker; signed award resolution; oversaw entire procurement process |

| Vicente Cecilio Fernández Guerrero | Influence Peddling (author), Prevarication (inducer), Administrative Fraud, Embezzlement | Secretary General, Ministry of Innovation, Science and Employment | Central coordinator between private interests and public officials; made coordinating phone calls |

| Pastor Sánchez de la Cuesta Sánchez de Ibargüen | Prevarication, Influence Peddling, Administrative Fraud, Embezzlement | Attorney of the Andalusian Government, Ministry lawyer | Legal expert who endorsed irregular decisions; prepared defensive reports |

| José Marcos Acosta Plaza | Prevarication, Influence Peddling, Administrative Fraud, Embezzlement | Delegate Comptroller, Ministry of Finance and Public Administration | Financial oversight; certified actions of contracting committee despite irregularities |

| Alberto Fernández Bueno | Prevarication, Influence Peddling, Administrative Fraud, Embezzlement | Head of Mining Area, Technical Commission member | Technical evaluations that improperly favored Minorbis-Grupo México |

| Juan José García Bartolomé | Prevarication, Influence Peddling, Administrative Fraud, Embezzlement | Technical Commission member, Head of Protected Natural Areas Service | Environmental compliance evaluation; assessed technical capacity of bidders |

| Aurora Gómera Martínez | Prevarication, Influence Peddling, Administrative Fraud, Embezzlement | Senior Engineering Corps official, Technical advisor for restoration impacts | Evaluation of restoration plan sections; technical quality assessments |

| Luis Cordero González | Prevarication, Influence Peddling, Administrative Fraud, Embezzlement | Senior Faculty of Biologists official | Co-authored restoration plan evaluation with Manuel Gil; biological impact assessment |

| Manuel Gil Calderón | Prevarication, Influence Peddling, Administrative Fraud, Embezzlement | General Administrators Corps official, Environmental protection service | Joint evaluation of restoration plans; environmental protection responsibilities |

| María del Pilar Orche Amaré | Prevarication, Influence Peddling, Administrative Fraud, Embezzlement | Senior Faculty of Engineers Corps official, Technical advisor on mining planning | Assessment of technical capacity and mining planning aspects |

| Juan Manuel Revilla Delgado | Prevarication, Influence Peddling, Administrative Fraud, Embezzlement | Secretary of the Contracting Committee | Procedural documentation; ensuring proper commission procedures |

| Julio Ramos Zabala | Prevarication, Influence Peddling, Administrative Fraud, Embezzlement | Member of contracting committee, Ministry of Finance and Public Administration representation | Committee member involved in decision-making process |

| José Salvador Camacho Lucena | Prevarication, Influence Peddling, Administrative Fraud, Embezzlement | Secretary General of Environment and Land Management, Territorial Delegation | Environmental assessments and land management oversight |

| Iván Maldonado Vidal | Prevarication, Influence Peddling, Administrative Fraud, Embezzlement | Head of Mining Service, General Directorate of Industry, Energy and Mines | Mining operations oversight and technical evaluations |

| Mario López Magdaleno | Influence Peddling (author), Prevarication (inducer) | Private individual, Magtel Group representative | External influence on procurement process through Vicente Fernández Guerrero |

| Isidro López Magdaleno | Influence Peddling (author), Prevarication (inducer) | Private individual, Magtel Group representative | External influence on procurement process through Vicente Fernández Guerrero |

¶ The Public Prosecutor

The role of the Public Prosecutor (Fiscalía) in the Aznalcóllar case has been controversial from the outset. Rather than serving as a driving force in the investigation of alleged corruption, the prosecutor’s office has repeatedly sought to dismiss, dilute, or derail the proceedings — often in stark contrast to both the investigative judges and the private accusers.

¶ Historical Obstruction

The criminal case against Minorbis–Grupo México and Andalusian officials was not initiated by the Fiscalía, but by a private prosecution brought by Emerita Resources and Ecologists in Action. From the beginning, the prosecutor’s stance has been reluctant and obstructive:

During the investigative phase, Fiscalía filed multiple requests to shelve the case, claiming insufficient evidence despite clear documentation of procedural irregularities.

These requests were rejected by both Judge Patricia Fernández and Judge Mercedes Alaya, who allowed the case to proceed based on detailed evidence of influence peddling and administrative fraud.

The 2021 indictments issued by Judge Alaya were clear in their criticism of the prosecution's stance, effectively positioning the court and private accusers as the primary guardians of accountability.

¶ Trial Conduct and Acquittal Requests

Throughout the oral phase of the trial (2025), the Fiscalía has:

- Repeatedly requested acquittals for several key defendants — reportedly at least seven separate times during trial proceedings.

- Chosen not to engage substantively with key evidence, such as the email trail or the timeline of the April 11 phone call from Vicente Fernández.

- Remained passive in courtroom exchanges, often allowing private prosecutors (such as Emerita's counsel, Ramón Escudero Espín) to lead direct examination and closing arguments.

On July 8, 2025, the prosecutor formally reiterated her position during closing remarks, once again requesting dismissal and acquittal. The statement provoked sharp criticism from observers and legal commentators, who viewed it as a final attempt to suppress judicial momentum. A widely circulated quote from one analyst described the stance as:

“A sustained optics strategy shaped by political pressure, institutional risk-aversion, and an enduring unwillingness to fully pursue convictions that would implicate powerful figures.”

¶ Legal Consequence: None

Crucially, under Spanish law, judges are not bound by the prosecutor’s recommendations. The judicial panel has full authority to:

- Convict any or all of the 16 defendants based on the evidentiary record.

- Ignore the prosecution’s position if it contradicts the facts or fails to account for the legal structure of the case.

Observers widely agree that the strength of the judicial record, not the prosecutor’s position, will determine the verdict. The public prosecutor's stance has thus become a symbol of institutional inertia, while the private prosecution has driven the case forward — legally, factually, and morally.

¶ The Private Prosecutor

In the Aznalcóllar case, the private prosecutor — Emerita Resources Corp., represented by legal counsel Ramón Escudero Espín — has played a central and proactive role, effectively carrying the legal weight of the prosecution in the face of an often-obstructive public prosecutor. Under Spanish law, acusación particular (private prosecution) allows an aggrieved party to initiate and pursue criminal proceedings independently — and in this case, Emerita’s involvement has been the primary force sustaining the legal action over nearly a decade.

¶ Role in Initiating the Case

Emerita Resources first filed a legal challenge in 2015, shortly after the Aznalcóllar tender was awarded to Minorbis–Grupo México. The challenge cited:

- Irregularities in the award process.

- Breaches of transparency and administrative law.

- A conflict of interest arising from the last-minute introduction of Minera Los Frailes SL, a shell company controlled 97% by Grupo México and just 3% by Minorbis.

When the Public Prosecutor declined to act, Emerita filed directly with the court, triggering the formal investigative phase. This led to the involvement of Judge Patricia Fernández and later Judge Mercedes Alaya, who validated the complaints and ordered indictments.

¶ Strategy in Court

Emerita’s legal counsel, Ramón Escudero Espín, has:

- Presented exhaustive technical and legal arguments.

- Cross-examined key defendants.

- Exposed contradictions between earlier statements and trial testimony — most notably the reversal by Vicente Fernández regarding the pivotal April 11, 2014 phone call.

Escudero’s final closing argument on July 8, 2025, was widely praised by courtroom observers for its clarity and force.

“2 hours and 23 minutes in closing, great job Ramón! The evidence and witness testimony and the multiple contradictions from the defendants is unchallengeable. We have won this.”

Unlike the Public Prosecutor, Escudero has placed significant emphasis on:

- The email trail between officials and Minorbis/Grupo México.

- The timeline inconsistencies in the López meeting and subsequent phone call.

- The irregular legal standing of Minera Los Frailes at the time of the award.

¶ Legal Standing and Objective

As private prosecutor, Emerita is pursuing:

- Criminal convictions for the 16 defendants.

- Administrative reversal of the original concession award.

- Reassignment of the Aznalcóllar mining rights to Emerita Resources — the original runner-up in the 2014 tender.

The company’s legal strategy is backed by a 2015 administrative appeal and multiple civil filings which position Emerita as the sole compliant bidder. These run parallel to the criminal case and reinforce the plausibility of an eventual reassignment.

¶ In Summary

The private prosecution in this case is not peripheral — it is foundational. Emerita Resources, through its legal team, has built and sustained the entire judicial process that now threatens to unravel one of Spain’s most controversial public tender decisions. While prosecutors wavered, the private prosecutor pressed forward — and in doing so, may have shaped the future of Aznalcóllar and redefined corporate accountability in Spanish mining law.

¶ The Mayor

At the heart of Aznalcóllar’s public story stands Juan José Fernández, the long-serving mayor of Aznalcóllar and a former miner himself. A figure of deep emotional resonance for the local community, Fernández has been a symbolic and vocal supporter of reactivating the mine — but not necessarily of the legal process behind the tender.

¶ A Miner Turned Mayor

Fernández led the 2009 protest when former Boliden miners camped inside Seville’s cathedral for 263 days following layoffs. During that time, he vowed that he would one day return to the cathedral in gratitude if the mine reopened. When the Minorbis–Grupo México tender was awarded in 2015, he honoured that promise with a thanksgiving mass in June 2025 — a moment documented by journalists as a “historic closure” for the town’s suffering miners.

He was elected mayor in the wake of the Boliden fallout and has served under the Izquierda Unida (United Left) coalition ever since. His role is not judicial but cultural and political: he is the emotive voice of the town’s longing for jobs, economic recovery, and mining identity.

¶ Public Position and Tone

Despite the controversy surrounding the tender, Fernández has consistently supported the reopening under Minera Los Frailes. His tone has been conciliatory and celebratory — praising the investment and potential of Grupo México’s plans. He is not believed to have been involved in the tender process itself and has not been implicated in the legal proceedings.

His presence at public ceremonies — including alongside representatives of Grupo México, political figures, and business leaders — signals a desire to unify the town behind whichever outcome brings jobs, regardless of judicial controversy. This position has occasionally put him at odds with Emerita’s supporters, who see the original tender as structurally invalid.

¶ Emotional Symbolism

Journalists have frequently referred to Fernández as “a unique mayor” and “a manual of good leadership,” highlighting his loyalty to the miners, his emotional resonance in public speeches, and his ability to represent Aznalcóllar as both victim and survivor. However, critics note that his emphasis on symbolic closure may sidestep the legal and ethical questions at the heart of the tender.

¶ Legacy and Relevance to the Case

While the mayor holds no legal sway in the outcome of the criminal trial, his public image has been leveraged by the defence narrative — projecting local legitimacy and popular support for the Minorbis–Grupo México award. Yet the legal question remains separate: even a grateful town does not override the statutory requirements of a fair and transparent tender.

Fernández’s emotional legacy may endure — but whether his preferred version of the mine’s future survives judicial scrutiny remains to be seen.

¶ Ecologists in Action

Ecologistas en Acción has played a pivotal role as a private prosecutor and civic watchdog in the Aznalcóllar case. Unlike many environmental groups that focus solely on ecological impact, Ecologistas en Acción has been deeply embedded in the legal and administrative scrutiny of the 2015 tender award to Minorbis–Grupo México (Minera Los Frailes, MLF).

¶ Role in the Case

Ecologistas en Acción was one of the first organisations to formally challenge the legality of the tender process, raising objections that were later echoed by Emerita Resources and substantiated in multiple judicial rulings. Their legal standing is not merely symbolic: they are a private accuser (acusación popular) in the criminal trial — an officially recognised party alongside Emerita, with full rights to present evidence, call witnesses, and make legal submissions.

Their core allegations have focused on:

- Fraudulent awarding of the tender to a company (MLF) that did not legally exist at the time of the award.

- Failure to meet minimum solvency and experience criteria by Minorbis and Grupo México.

- Suspicions of influence peddling and administrative irregularities surrounding the creation and registration of Minera Los Frailes SL just days before formal acceptance of the award.

- Lack of environmental authorisation and transparency, contrary to Spanish mining law and EU environmental directives.

¶ Contribution to Key Revelations

One of Ecologists in Action's most significant contributions was uncovering the existence of two separate award resolutions dated 25 February 2015 — one issued to Minera Los Frailes (which had not yet been formed) and another, now missing from the registry, allegedly granted to Minorbis–Grupo México. They submitted this to the court along with documentation from the Andalusian Mining Registry, directly challenging the legal basis for the award.

Their legal submissions were among the first to clearly articulate the chain of concealment and improper delegation, later echoed by Judge Alaya in her 2021 indictment.

¶ Alignment with Emerita

Though Emerita Resources has taken a leading role in the private prosecution, Ecologistas en Acción has been a consistent and credible ally, particularly in matters of environmental compliance, registry fraud, and procedural integrity. Their involvement has helped ground the legal challenge in broader public interest terms, extending beyond corporate competition to include transparency, accountability, and environmental justice.

¶ Public and Legal Credibility

Unlike politically affiliated actors or corporate litigants, Ecologists in Action is seen by many in the media and judiciary as an independent civil society actor. Their reputation for detailed research and procedural rigour has boosted the credibility of the prosecution, especially in the early stages of the investigation when institutional support was weak and the Fiscalía (public prosecutor) remained hesitant.

¶ PSOE

The Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE), Spain’s long-dominant centre-left party, is not a formal defendant in the Aznalcóllar trial — but its fingerprints are all over the case. The scandal unfolded during the tenure of the PSOE-controlled Junta de Andalucía, and many of the individuals accused of corruption, influence peddling, or administrative fraud were senior PSOE appointees or functionaries at the time of the 2015 tender award.

¶ Institutional and Political Involvement

Susana Díaz, then-President of the Junta de Andalucía and a leading PSOE figure, presided over the government that awarded the Aznalcóllar tender to the Minorbis–Grupo México consortium. While not personally indicted, the political structure she led is widely viewed as having enabled or turned a blind eye to the alleged manipulation of the process.

Vicente Fernández Guerrero, former head of SEPI (Spain’s State Industrial Holding Company), is one of the key defendants. A PSOE loyalist, he later took up roles tied to Santos Cerdán, another senior party operative and confidant of Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez. Fernández is alleged to have placed a key phone call to Emerita’s president on 11 April 2014 — a central act in the influence-peddling chain.

Santos Cerdán himself, though not formally connected to the Aznalcóllar trial, was arrested in a separate corruption scandal in 2025 and is now remanded in prison. His proximity to other figures implicated in the Aznalcóllar affair has fuelled speculation about the depth and systemic nature of PSOE-linked influence networks during that period.

¶ Party Response and Internal Fallout

The party's response to the Aznalcóllar case has evolved from silence to distancing. In early phases of the trial, there were minimal public statements from PSOE leadership, with an apparent effort to treat the scandal as a technical matter rather than a political failure. However, with mounting courtroom evidence and the recent judicial clampdown on broader PSOE-linked corruption, cracks have begun to show:

- Historical PSOE members have publicly criticised current leadership, with some calling for Sánchez’s resignation in light of the optics and institutional degradation.

- Internal party sentiment, according to media reports, is at a low point — marked by shame and exhaustion as scandals pile up.

The Fiscalía’s persistent reluctance to support the case is widely perceived by observers as a remnant of political interference from PSOE-aligned judicial officials. Though never directly confirmed, the perception has become difficult to ignore.

¶ Reputational Damage and Broader Impact

The Aznalcóllar case has become a symbol of the PSOE’s waning credibility in Andalusia, where the party once held unshakeable control. Its ties to the award process, both direct and institutional, have compounded the public’s sense of betrayal — especially in a region still scarred by the Boliden disaster of 1998.

The party now faces an uncomfortable legacy: even if it survives electorally, the case has exposed what many see as a deeply ingrained culture of backdoor dealing, procedural shortcuts, and institutional capture.

¶ The “Plumber” (Fixer)

In the context of the Aznalcóllar corruption trial, the term "plumber" — a Spanish slang shorthand for a behind-the-scenes operator or political fixer — has come to symbolize the unofficial but essential conduits of influence that made the alleged rigging of the tender possible. While there is no single defendant formally designated as “the plumber,” the role is widely believed to have been shared or passed among several insiders, particularly those who moved between political appointments, commercial partnerships, and opaque advisory roles within the Junta and affiliated companies.

¶ Key Functions of the Fixer

The "plumber" is not a public official in the traditional sense, but rather someone who:

- Orchestrates communications between political actors and private bidders while maintaining plausible deniability.

- Facilitates early access to confidential documents and pre-tender data for favoured participants.

- Ensures contractual flexibility and paper trails are manipulated to legalise otherwise irregular decisions.

- Receives compensation through indirect means — e.g. consulting fees, payments to shell companies, or board appointments.

¶ Alleged Fixer Networks in Aznalcóllar

In the Aznalcóllar case, this role is most often associated with Minorbis, the Cordoba-based subsidiary of Magtel that partnered with Grupo México. Several individuals from the Minorbis–MLF structure are believed to have acted as conduits for influence, with connections deep into the Andalusian PSOE apparatus. Specific allegations include:

- Transfer of ownership: Grupo México never submitted a Phase 2 bid, but through a last-minute legal maneuver, the contract was granted to Minera Los Frailes SL — a shell company that didn’t exist at the time of award but was later constructed from a corporate shell by AMC Iberia (itself controlled by Grupo México).

- Role of Magtel: Multiple reports and testimony suggest Magtel’s principal contribution to the joint bid was not technical capability but lobbying access and insider positioning — classic fixer behaviour.

- Alleged payments: Judicial filings and media investigations have pointed to unusual financial transfers from AMC to Minorbis totalling over €1 million, with the possibility of additional sums tied to lobbying or “success fees.”

¶ Cultural Symbolism and Trial Narrative

The metaphor of the “plumber” has persisted throughout the case not only because it encapsulates the murky mechanics of political favouritism, but also because it exposes how the system was built to reward insiders. Fixers are not merely tolerated; in some political ecosystems, they are essential infrastructure.

In court, the defence has repeatedly tried to dismiss these roles as legitimate consulting arrangements. But the sequence of creation, ownership, and influence surrounding entities like Minorbis, AMC, and MLF suggests otherwise. The “plumbing” — hidden but functional — is now exposed by the burst pipe of the trial itself.

Prosecutor’s Office Supports Investigating Leire Díez | Analysis

¶ The Judges & Courts

¶ Judicial Oversight and Independence

The integrity and independence of the Spanish judiciary have played a decisive role in the progression of the Aznalcóllar case. Despite the Public Prosecutor’s repeated attempts to downplay or dismiss the charges, it has been the judges — particularly those involved in the investigative and appeals phases — who have ensured the case moved forward. Their rulings form the legal backbone of the 2025 oral criminal trial and underpin Emerita’s claim to the project via administrative appeal.

¶ 7th Provincial Court of Seville

In October 2016, the 7th Provincial Court of Seville issued a significant ruling in favor of Emerita Resources Corp. regarding the Aznalcóllar public tender process. This ruling was a pivotal moment in the company’s legal battle over alleged irregularities in the awarding of the Aznalcóllar mine tender in 2015. The court, in a unanimous 59-page judgment by four judges, reopened the case after a lower court had dismissed it, finding sufficient evidence of potential criminal acts.

¶ Evidence of Irregularities

The court identified serious issues in the tender process, including the competing bidder’s (Minorbis-Grupo México) failure to submit required documentation, the tender panel’s neglect to evaluate technical merits properly, and the unlawful awarding of mining rights to Los Frailes Mining, a company that did not participate in the tender. This validated Emerita’s claims of corruption and procedural misconduct. [LINK]

¶ Reopening of the Criminal Case

The Provincial Court’s decision to overrule the lower court’s dismissal and instruct the lower court to reinvestigate the case marked a critical step forward. It established that there was strong evidence of gross negligence and misconduct, supporting Emerita’s allegations of crimes such as prevarication, influence peddling, and fraud.[LINK] [LINK]

¶ Strengthening Emerita’s Legal Position

The ruling reinforced Emerita’s standing as a legitimate plaintiff, affirming its right to challenge the tender process. It also highlighted that Minorbis’ bid did not meet the tender’s criteria and should have been disqualified, positioning Emerita as the only qualified bidder. Under Spanish law, if a tender is found to be awarded through criminal acts, it must be voided and awarded to the next qualified bidder, which is Emerita.[LINK] [LINK]

¶ Path to Potential Tender Award

The ruling brought Emerita closer to securing the Aznalcóllar project, a world-class zinc-lead-silver mine. The court’s findings suggested that a successful outcome in the criminal case could lead to the disqualification of the Minorbis-Grupo México bid, potentially granting Emerita the mining rights. This was a significant step toward developing the Aznalcóllar property as a modern, environmentally responsible mining operation.[LINK] [LINK]

In summary, the 2016 ruling by the 7th Provincial Court of Seville was a crucial victory for Emerita Resources, as it validated their claims of corruption, reopened the criminal investigation, and strengthened their legal standing to potentially secure the Aznalcóllar mine tender, setting the stage for further legal proceedings that continued into 2025.

- October 2016 - 7th Provincial Court of Seville :: Spanish | English translation

¶ Judge Mercedes Alaya (Investigative Court No. 6)

Judge Alaya is widely recognised as the most pivotal legal figure in the Aznalcóllar case. Her seminal opinion issued on 26 May 2021, spanning nearly 100 pages, meticulously documented:

Structural irregularities in the tender;

- Political interference and coordination between Junta officials and Minorbis;

- The creation of shell entities such as Minera Los Frailes (MLF) post-award;

- And the post-submission manipulation of scoring criteria.

Alaya found that Minorbis was:

- Created solely for the tender,

- Capitalised with just €3,000,

- Lacking any demonstrated technical or financial solvency.

She concluded that Junta officials knowingly allowed Minorbis to proceed and win the tender, despite knowing it failed both legal and technical qualification thresholds.

Key excerpts:

“The entity Minorbis was created expressly for the contest, with no experience, €3,000 in capital, and no demonstrated solvency. The decision to allow them to proceed—despite lacking both legal and technical qualifications—was taken with full knowledge of its patent illegality.” (5-26-21 Opinion, p.9)

“The judicially supported inference is that the process was rigged from the outset. There is sufficient basis to indict senior officials for abuse of office, influence peddling, and embezzlement via disloyal management.” (5-26-21 Opinion)

Alaya also referenced:

- A confirmed phone call from Vicente Fernández Guerrero, then Minister of Innovation, to Emerita's president — made within minutes of Minorbis' approach regarding a joint bid — described as evidence of insider coordination;

- The post-dated creation of MLF after the award;

- The absence of a signed award resolution, rendering the award legally questionable.

Her legal conclusion described the affair as “chained influence peddling,” and she explicitly dismissed the Public Prosecutor’s repeated motions for acquittal, calling the evidence “overwhelming and compelling.”

- May 26, 2021 - Spanish | English translation

¶ Judge Patricia Fernández (Court of Instruction No. 3)

Judge Fernández played a vital role in carrying the case into the oral trial phase. On 25 June 2021, she issued a ruling that:

- Expanded the number of defendants from 9 to 16,

- Adopted Alaya’s legal reasoning in full,

- And confirmed that the facts justified escalation to trial.

She ruled:

“There was objective, sustained interference in the contracting process with intent to ensure Minorbis’s success… Criteria were altered mid-process, legal deadlines were violated, and tender protocols ignored.” (6-25-21 Opinion, p.11)

Fernández also highlighted:

- False attribution of financial solvency via Grupo México;

- Legal non-compliance in the creation of MLF;

- And the missing signed tender resolution, a necessary legal element for valid award.

- Her opinion formally committed all 16 accused to oral trial.

Jun 25, 2021 - Spanish | English translation

¶ Seville Provincial Court No. 3 (Appeals Panel) – 27 May 2021

Following appeals from several defendants and the Public Prosecutor, this three-judge appellate panel unanimously upheld Judge Alaya’s and Fernández’s findings.

They rejected attempts to annul the investigation and instead reaffirmed the criminal charges:

- Prevaricación (abuse of public office),

- Influence peddling,

- Embezzlement,

- Fraud against the administration.

“Given the body of evidence that exists provisionally… the appeal must be dismissed. The decisions to promote Minorbis and award the tender despite patent disqualifications cannot be seen as legal, rational, or administratively defensible.” (5-27-21, Provincial Court Opinion)

May 27, 2021 - Spanish | English translation

¶ Criminal Trial Judges

The composition of the judicial panel is one of the most critical factors in politically sensitive trials. In this case, the three magistrates of Criminal Chamber No. 3 of the Provincial Court of Seville bring a combined profile of judicial independence, procedural rigor, and ethical track records—offering strong reassurance to investors that the trial is being handled with integrity and seriousness.

¶ Ángel Márquez Romero (Presiding Judge)

Current Role: Presiding Judge of Criminal Chamber No. 3

Judicial Standing: Senior judge with multiple years of service in Seville’s Provincial Court

Judicial Profile:

- Lead Role: As presiding judge, Márquez anchors the trial. He was also one of the judges who validated the reopening of the Aznalcóllar case, aligning with the findings of Judge Mercedes Alaya after prior attempts to archive the case.

- Legal Trajectory: Trusted within the court system, having served in other high-profile chambers. Known for steady leadership and facilitating clear decisions in complex criminal panels.

- Judicial Temperament: Regarded as balanced and reserved—prioritizing evidentiary consistency over external narratives. Has been fearless in previous high profile corruption trials.

Now the lead judge in the Aznalcóllar tender criminal trial, Ángel Márquez Romero was also the investigating judge in the Guerra Case, in which Juan Guerra (brother of then Vice President Alfonso Guerra - Felipe González was President) was convicted in 1995 and sentenced to two years jail plus large fines. Anti-corruption actions don’t get any bigger than that!

- Family History: Long family history of prestigious judicial positions.

"And finally, Ángel Márquez Romero, one of the sons, just like his brothers, inherited the magisterium of his father and now holds the Presidency of Section Three, Criminal Division, in which I too had been active. Just as his progenitor, he knew how to pass down the professional vein to his son Ángel Márquez Prieto, who practices law with intelligence and brilliance in the sphere of what was once the prestigious magistrate (now retired) Don Alfonso Martínez Escribano." (PDF)

Why It Matters:

- His leadership ensures cohesion and procedural focus in the panel’s deliberations. His prior vote to move the case forward offers reassurance that the trial will not be quietly dismissed or derailed procedurally.

In addition to being one of the judges with the most tenures in Seville, Márquez is a well-known judge in Seville. He became famous for his role as the investigator in the Juan Guerra case , which involved the alleged influence peddling of an office launched by the brother of the then Vice President of the Government, Alfonso Guerra, which also cost the latter his job. Over the years, Márquez has presided over numerous high-profile trials from the Seville Court. These include the Mercasevilla case and the case of the former Betis manager, Manuel Ruíz de Lopera.

¶ Luis Gonzaga de Oro-Pulido Sanz

Born: 1962, Madrid

Role: Magistrate, Criminal Chamber No. 3, Provincial Court of Seville

Notable Trait: First judge in Spain to use a guide dog due to retinitis pigmentosa

Guide Dog: Pusky, trained by ONCE Foundation

Judicial Profile:

- Career Track: Longtime criminal judge from a family of jurists. Technically rigorous and methodical in ruling.

- Integrity: Known for upholding judicial ethics. Recused himself in 2016 from the high-profile Lopera case due to a perceived conflict of interest—without pressure or accusation.

- Public Image: Symbol of resilience and professionalism. Embraced visual disability while maintaining excellence in judicial performance.

- Ethical Standing: No known reputational issues or political affiliations. Consistently regarded as a quiet force of judicial impartiality.

Why It Matters:

- His presence signals procedural fidelity and judicial independence. Investors can take comfort in the legal integrity anchoring the panel. His deep knowledge of Spanish criminal law and refusal to bend to outside influence are clear assets in a corruption trial of this magnitude.

Details:

Luis Gonzaga de Oro-Pulido Sanz, born in Madrid in 1962, is a magistrate at the Provincial Court of Seville. He comes from a family with a strong legal tradition; his grandfather and several uncles were judges, and two of his siblings have also pursued careers in the judiciary.

De Oro-Pulido has been affiliated with the ONCE (National Organization of Spanish Blind People) since 2004 due to retinitis pigmentosa, a degenerative eye condition. In 2018, he began using a white cane, and in 2023, he became the first judge in Spain to work with a guide dog, Pusky, a black Labrador trained by the ONCE Foundation.

Professionally, de Oro-Pulido is known for his meticulous approach to casework. He has described his routine as involving extensive study and thorough examination of case materials to ensure fair and just rulings. His colleagues have noted his dedication and resilience, particularly in adapting to his visual impairment without compromising his judicial responsibilities.

➕ Career Track: De Oro-Pulido comes from a family of judges and has spent decades in criminal law, currently serving in Criminal Chamber No. 3 of Seville’s Audiencia Provincial. His rulings are known for being technically grounded and procedurally rigorous.

➕ Personal Integrity: He is widely respected for his perseverance. Diagnosed with retinitis pigmentosa, a degenerative eye condition, he became the first judge in Spain to work with a guide dog. This speaks to his deep personal discipline and adaptability—qualities that often translate into steady, principled professional judgment.

➕ Public Image: Far from being a political insider or compromised figure, de Oro-Pulido's public image is that of a civil servant devoted to judicial independence and quiet excellence.

Manuel Ruiz de Lopera Case (2016):

Role: De Oro-Pulido was initially appointed as the reporting judge (ponente) for the criminal case against Manuel Ruiz de Lopera, former president of Real Betis, concerning alleged mismanagement of the club from 1993 to 2008. The case, investigated by Judge Mercedes Alaya, involved accusations of financial misconduct and decapitalization of the club for the benefit of Lopera’s companies, Tegasa and Encadesa. Action: De Oro-Pulido recused himself from the case due to a close friendship with Adolfo Cuéllar, president of the League of Betis Jurists, one of the complainants. Judge Ángel Márquez Romero replaced him as the reporting judge.

Significance: His recusal demonstrates adherence to judicial ethics to avoid conflicts of interest, and there is no indication of impropriety or corruption on his part. The case itself is unrelated to any allegations against de Oro-Pulido.

Judicial Conduct: De Oro-Pulido is described as a disciplined and professional magistrate, with colleagues and court staff supporting his integration of Pusky into the workplace. His comments in interviews reflect a focus on judicial impartiality, stating that public opinion about his ability to perform his duties due to his visual impairment does not concern him, as his work is well-regarded within Seville’s legal community.

Why It Matters: This is a textbook example of ethical judicial conduct. Rather than remain silent, de Oro-Pulido voluntarily stepped back to preserve the impartiality of the court and uphold due process.

Why It’s Relevant for Emerita Investors: This history should increase investor confidence in his current role on the Aznalcóllar panel:

Demonstrates Judicial Ethics: He acted with integrity even when there was no direct accusation or pressure. This reinforces the view that he’s not someone who bends to influence.

Shows Self-Awareness: His willingness to recuse signals an understanding of how perceived conflicts can erode public trust—critical in a politically sensitive corruption trial like Aznalcóllar.

Track Record of Independence: Rather than being tied to powerful interests or acting as a “bought judge,” this past behavior aligns with an impartial, clean judiciary—exactly what Emerita’s legal position needs.

¶ Carmen Pilar Caracuel Raya

Current Role: Magistrate, Criminal Chamber No. 3, Provincial Court of Seville

Judicial Experience: Over 30 years across multiple jurisdictions (Catalonia, Andalusia)

Judicial Profile:

- Extensive Background: Former posts in juvenile, mixed, and instruction courts; later appointed to the Provincial Court of Málaga and then to Seville.

- High-Profile Cases: Presided over a 2023 double homicide trial that resulted in a 38-year sentence; also involved in complex political subsidy fraud cases (e.g., UGT-Andalucía).

- Professional Resilience: A 2008 prevaricación complaint was reviewed and dismissed by the CGPJ with no disciplinary action. No misconduct has been recorded since.

- Institutional Standing: Member of the Professional Association of the Magistracy (APM)—a conservative, constitutionally grounded judicial association. In 2025, she was a candidate for presidency of the Seville Court.

Why It Matters:

- Her experience with politically charged cases adds weight to the trial’s credibility. She is viewed as procedurally grounded, ethically vetted, and immune to populist or institutional pressure. Her APM affiliation also signals alignment with legal orthodoxy, not ideological bias.

Details:

Carmen Pilar Caracuel Raya is a seasoned Spanish magistrate currently serving in Criminal Section No. 3 of the Provincial Court of Seville. Her judicial career spans over three decades, marked by a progression through various courts across Spain.

Judicial Career and Reputation:

Caracuel began her legal career in Catalonia, serving in the Mixed Courts No. 4 of Cornellà and Sant Feliu de Llobregat. She later held positions in the Juvenile Court No. 1 of Almería and the Court of Instruction No. 14 of Málaga. In 2015, she was appointed to the First Section of the Provincial Court of Málaga, and by the end of 2020, she joined the Provincial Court of Seville.

Colleagues describe Caracuel as meticulous and dedicated, often engaging in extensive study to ensure fair and just rulings. Her approach to casework is characterized by thorough examination of evidence and adherence to legal protocols.

Notable Cases and Judicial Conduct:

Throughout her career, Caracuel has presided over complex and high-profile criminal cases. Notably, in 2023, she oversaw a jury trial resulting in a 38-year prison sentence for a woman convicted of murdering two neighbors in Dos Hermanas. Additionally, she has been involved in cases concerning subsidy fraud involving the leadership of UGT-Andalucía, demonstrating her capacity to handle cases with significant political and public interest.

Ethical Considerations

In 2008, Caracuel faced a legal challenge when a property owner accused her of prevarication for allegedly archiving a case without sufficient investigation. The Superior Court of Justice of Andalusia (TSJA) admitted the complaint and initiated preliminary proceedings. Caracuel defended her actions, stating that her decision was based on legal grounds and that any perceived errors could be addressed through standard appeals. The General Council of the Judiciary (CGPJ) reviewed the case and, finding the evidence insufficient, did not proceed with disciplinary action.

Professional Associations and Leadership:

Caracuel is affiliated with the Professional Association of the Magistracy (APM), a prominent conservative judicial association in Spain. She has also been involved in the APM's executive committee, reflecting her active participation in the judicial community. In 2025, Caracuel was among six candidates vying for the presidency of the Provincial Court of Seville, a position that, if secured, would make her the first woman to hold this role. Summary Judge Carmen Pilar Caracuel Raya's extensive experience, commitment to judicial ethics, and involvement in significant cases position her as a respected figure within the Spanish judiciary. While she has faced challenges, her career reflects a dedication to upholding the law and ensuring justice.

Investor Takeaway:

Judge Caracuel’s record reflects judicial competence, institutional experience, and a strong procedural backbone. Her inclusion on the Aznalcóllar panel bodes well for Emerita investors seeking a fair trial grounded in rule of law rather than political expediency. While conservative in her judicial affiliation, she is also seasoned, ethically vetted, and used to navigating cases with political overtones. Like her fellow magistrates Márquez and de Oro-Pulido, she reinforces the view that this panel is well-equipped to resist external pressure and rule decisively based on evidentiary weight.

Profile Summary:

Carmen Pilar Caracuel Raya is one of the three magistrates presiding over the Aznalcóllar criminal trial. She brings over three decades of experience in Spain’s judicial system, with a strong background in complex criminal cases—including high-profile homicides and political subsidy fraud.

➕ Extensive Judicial Experience: She has served across multiple jurisdictions (Catalonia, Andalusia), handling instruction, juvenile, and criminal courts. Her current role in Criminal Chamber No. 3 of the Audiencia Provincial de Sevilla positions her at the center of high-impact cases.

➕ Tough on Crime: Known for presiding over a 38-year conviction in a double homicide case, Caracuel has shown she does not shy away from severe sentencing when evidence is strong.

➕ Ethical Record: A 2008 complaint against her for prevaricación (misuse of office) was reviewed and ultimately dismissed by the CGPJ, Spain’s top judicial authority. There was no sanction, and no subsequent misconduct has been reported.

➕ APM-Aligned: She is part of the Professional Association of the Magistracy (APM), a conservative-leaning but highly institutional judicial association in Spain, suggesting strong alignment with legal orthodoxy and constitutional process.

➕ Leadership Track: In 2025, she was one of six candidates for the presidency of the Provincial Court of Seville—indicating both her seniority and professional credibility among peers.

¶ Investor Takeaway

The judicial panel in the Aznalcóllar criminal trial is arguably above average in quality, integrity, and experience, especially for a case entangled with political history. All three judges have:

- Clean reputations with no links to the Junta de Andalucía or Grupo México

- Experience in complex criminal proceedings

- A shared pretrial stance that favored letting the case proceed

Together, they form a panel that is:

- Highly likely to rule based on evidentiary weight and legal merit—rather than political expediency.

- This configuration significantly de-risks the judicial process for Emerita investors and strengthens confidence in a lawful, transparent outcome.

¶ The Litigation

¶ Summary of Judicial Findings

Across three courts and five judges, the Spanish judiciary consistently reached the following conclusions:

The 2014 Aznalcóllar tender process was manipulated in favour of Minorbis–Grupo México.

Senior Junta officials engaged in illegal acts of interference, including:

- Use of shell entities and false solvency attributions,

- Backdating of documents,

- Scoring manipulation, and

- Circumvention of established procurement protocols.

Emerita, as the only other qualified bidder, remains the legally entitled successor to the tender under Spanish public procurement law.

These rulings were not isolated nor political in nature. As the Triple S Investing report notes, five separate judges across three levels of the Spanish court system reviewed the case and reached the same conclusion: crimes were committed and the tender must be annulled with Emerita standing as the valid successor.

This judicial consensus forms the evidentiary and legal foundation for both:

- The 2025 oral criminal trial that has just concluded, and

- The pending administrative reassignment of the Aznalcóllar project.

¶ Judicial Opinions

For documents and complete analysis visit the Court Document Analysis page HERE

¶ Reversal and Alignment – Judge Patricia Fernández

One of the most consequential shifts in the legal arc of the Aznalcóllar case came from Judge Patricia Fernández, who initially showed caution in prosecuting the full scope of alleged wrongdoing but ultimately issued a decisive June 25, 2021 opinion that not only advanced the case to oral trial but also fully aligned with the earlier legal reasoning laid out by Judge Mercedes Alaya.

This evolution is significant because Fernández had previously reviewed the same procedural file and, at one stage, appeared inclined to limit the scope or scale of the indictments. However, after the full evidentiary record was developed — including the UDEF investigation, witness testimony, technical commission records, and analysis of procurement law violations — she issued an expanded ruling that:

- Increased the number of defendants from 9 to 16,

- Expanded the number of charges from 3 to 4, and

- Directly adopted the “chained influence peddling” framework developed by Judge Alaya.

Fernández wrote that there had been:

“Objective, sustained interference in the contracting process with intent to ensure Minorbis’s success… Criteria were altered mid-process, legal deadlines were violated, and tender protocols ignored.”

(6-25-21 Opinion, p.11)

She cited the same core violations identified by Alaya, including:

- The false attribution of solvency to Minorbis via Grupo México, which lacked legal standing in the bid;

- The absence of a legally valid, signed tender resolution at the time of award;

- The incorporation of Minera Los Frailes (MLF) after the award was granted — a clear breach of public procurement law;

And the internal communications between Junta officials suggesting premeditated manipulation.

By adopting these elements, Judge Fernández not only confirmed the criminal viability of the case, but in effect rejoined the prosecutorial path championed by Alaya, revalidating the structure of the charges and sustaining the evidentiary bridge into the current oral trial.

This reversal is legally and symbolically important: it confirms that when confronted with the totality of the evidence, even initially hesitant judges converged on the same conclusion — that criminal acts were committed in the Aznalcóllar tender process, and that a full public trial was both necessary and justified.

¶ Administrative Court: Role and Status

The Administrative Courts have played a parallel but critical role in Emerita’s legal challenge to the Aznalcóllar tender. While the criminal case seeks to establish the commission of crimes by public officials and beneficiaries, the administrative track focuses on the legality of the tender process itself, with the power to annul the award and reassign the concession depending on the outcome.

¶ Jurisdiction and Function

The core forums for administrative review have been the Tribunal Administrativo de Recursos Contractuales de la Junta de Andalucía (TARCJA) and the Contentious-Administrative Courts of Seville.

These bodies assess whether the award process breached procurement law — specifically Ley 9/2017 (Public Sector Contracts Law) and Ley 22/1973 de Minas (Mining Law).

Their role is to evaluate legal challenges from losing bidders (including Emerita Resources and AMC Andalucía Mining SA) regarding procedural irregularities, unequal treatment, or violations of tender conditions.

¶ Key Issues Under Administrative Scrutiny

- Failure to Disqualify Minorbis–Grupo México (GM) for not meeting solvency and mining experience thresholds required under Article 71 of Ley 9/2017.

- Post-award substitution of the awardee: The rights were initially granted to Minorbis–GM but ultimately awarded to Minera Los Frailes (MLF) — a company that did not exist at the time and was formed weeks after the tender closed.

- Conflicting and altered award documentation: Two resolutions were issued (Resolution 7953 to Minorbis–GM and 7976 to MLF), one of which later disappeared from the Andalusian Mining Registry.

- Denial of equal access to public documentation and lack of transparency during the evaluation period — Emerita was denied key information used to justify MLF’s technical scores.

- Manipulation of scoring and weighting: Allegations that scoring was retroactively altered or inconsistently applied to favour Minorbis–GM.

¶ Precedent from IBW

Emerita has already successfully overturned a prior mining tender through this legal pathway. In the “IBW” case, Emerita won a landmark administrative ruling against the Junta’s award of a different mining project. The court found procedural manipulation and declared the tender null, forcing a re-tender that Emerita ultimately won. This win is seen as a critical precedent: it confirms that Andalusian authorities have a pattern of irregularities in mining tenders — and that the administrative courts are willing to overturn flawed awards when sufficient evidence is presented.

¶ Current Status

- The administrative court case for Aznalcóllar remains open but was paused pending the outcome of the criminal proceedings.

- Emerita’s administrative challenge — supported by AMC and others — seeks to invalidate the award and argues that if a crime is confirmed, the tender must be annulled.